Money — it’s a fundamental part of the economy, but the ways people use, spend, and save it can be quite complex. In the world of economics, two laws are often discussed in relation to how different types of money behave in the market: Gresham’s Law and Thier’s Law. While these laws sound similar, they operate under different conditions and assumptions, particularly when it comes to legal tender.

The key to understanding how these laws work lies in their application to currencies in circulation — especially when those currencies are both legally accepted as means of payment. Let’s dive into what each law suggests, and explore how legal tender status plays a central role in determining which law applies in different economic situations.

1. Gresham’s Law: Bad Money Drives Out Good

Gresham’s Law is often phrased as “bad money drives out good.” This principle explains a key phenomenon that occurs when two forms of money — both considered legal tender — circulate within an economy. According to Gresham’s Law, when people perceive one currency as less valuable or more unstable than another, they will typically spend the “bad” money and hoard the “good” money.

- How It Works: The condition for Gresham’s Law to take effect is that both forms of money must be legally recognized as valid payment. In simpler terms, both currencies must be considered legal tender — i.e., they must be accepted as a means of paying debts.

- Behavioral Impact: Gresham’s Law comes into play when a government issues two forms of money, but one is viewed as less stable or worth less than the other. As a result, people will spend the “bad” (less stable or lower-valued) money in their daily transactions and try to hold on to the “good” (more stable, more trusted) money, even if both are officially acceptable for payment.

- Example: Imagine a scenario where a government issues both paper money and gold coins as legal tender. If inflation devalues the paper money, people may lose trust in it, yet they’ll still be obligated to accept it in transactions. As a result, they will spend the paper money as quickly as possible, while hoarding the more stable gold coins, despite both currencies being legally acceptable forms of payment.

In this way, Gresham’s Law predicts that the “bad” money will stay in circulation while the “good” money will be withdrawn from the economy and hoarded by those who value it more.

2. Thier’s Law: Good Money Drives Out Bad

Thier’s Law is built on the opposite idea: “Good money drives out bad.” While Gresham’s Law focuses on immediate behaviors, Thier’s Law refers to a longer-term shift in preference when one form of money is perceived to be more stable and valuable than another. However, this law applies more effectively when legal reforms, changes in the monetary system, or a widespread shift in public perception occur.

- How It Works: Unlike Gresham’s Law, Thier’s Law does not rely on the coexistence of two forms of money as legal tender in the same way. Instead, it’s typically relevant in situations where one currency gradually replaces another, due to a perceived increase in stability or trustworthiness.

- Behavioral Impact: With Thier’s Law, people begin to favor the more stable currency (the “good” money) and eventually phase out or stop using the less stable form of money (the “bad” money), especially when reforms or market forces shift economic conditions.

- Example: A classic example would be when a government switches from using paper money to a more stable, gold-backed currency. Initially, both forms of currency may still be legal tender, but over time, as people realize that the gold-backed money is far more trustworthy and stable than the depreciating paper money, they will prefer to use the gold currency exclusively. Ultimately, the depreciated paper money will fade out of circulation as people lose confidence in it.

3. The Role of Legal Tender

Legal tender status is a crucial factor in how these two laws operate.

- In the case of Gresham’s Law: When both forms of money are legal tender, they continue to be used alongside each other, but the “bad” money remains in circulation because people spend it quickly and hoard the “good” money. This quick shift in how money is used is rooted in immediate public behavior driven by perceived value. Legal tender status doesn’t necessarily prevent this action — even if both currencies are accepted for payment, people instinctively seek the more valuable currency to hold.

- With Thier’s Law: If both currencies are legal tender, this does not always lead to the transition to one currency taking over the other. In fact, the application of Thier’s Law requires a shift in public confidence or the imposition of legal reforms to gradually make one currency the dominant form. Since both currencies are legally valid for transactions, Thier’s Law will likely not fully apply unless one form of money experiences legal or institutional changes, such as the replacement of one currency by another more stable option.

In simpler terms, Thier’s Law assumes that one currency will gradually replace the other as trust builds and public sentiment favors the more stable currency. But if both are legally recognized, Thier’s Law is unlikely to fully apply without additional shifts or reforms.

4. Are Gresham’s and Thier’s Laws Contradictory?

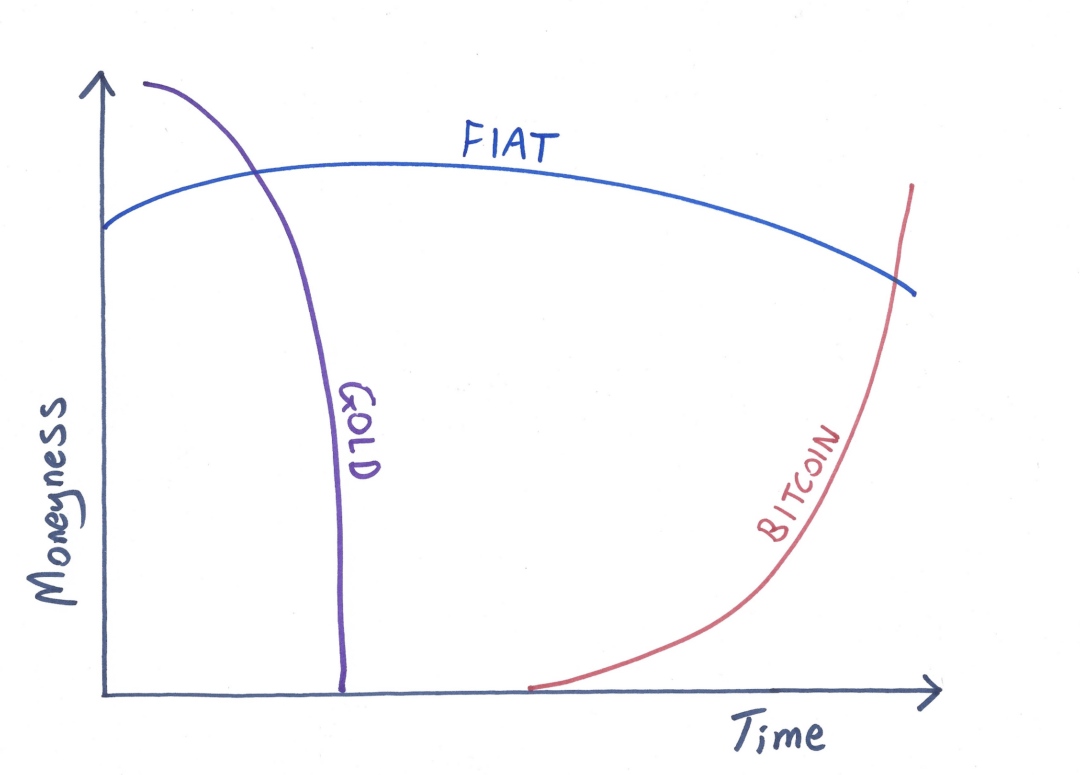

At first glance, it may seem like Gresham’s Law and Thier’s Law contradict each other. Gresham’s Law suggests that “bad” money stays in circulation because people will spend it and hoard “good” money. Thier’s Law suggests that over time, the more stable currency will overtake and displace the less stable one.

However, they actually operate on different timescales.

- Gresham’s Law describes immediate behavior, explaining how the bad money stays in circulation in the short term, while the good money is hoarded.

- Thier’s Law applies over the long term. It predicts that, after a gradual shift in trust and preference, the more stable currency will ultimately dominate, often after reforms are introduced, public perceptions change, or a currency becomes seen as more stable due to political or economic decisions.

Rather than being contradictory, these laws describe two different aspects of the relationship between multiple forms of legal tender. Gresham’s Law tends to describe quick, intuitive reactions to shifts in currency value, while Thier’s Law reflects longer-term market behaviors, where one form of currency overtakes the other after a fundamental change in confidence or system.

Conclusion: The Balance Between the Two Laws

In conclusion, both Gresham’s Law and Thier’s Law can coexist in a currency system, but they apply at different stages of the economic process. Gresham’s Law describes the immediate, often reflexive behaviors of individuals when they have access to two forms of currency, both of which are legal tender. Meanwhile, Thier’s Law operates when there’s a more sustained shift in the market or after legal reforms that gradually lead to the dominance of one currency over the other.

Both laws emphasize the role of public perception in shaping how currency is used, and they highlight the complex relationship between money, trust, and legal recognition. Understanding the role of legal tender in the application of these laws helps shed light on how money functions in any economy, both in the short and long term.

Discover more from Brin Wilson...

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.