We were told that technology would save us time. That it would make our lives easier, more efficient, more meaningful.

That was the great lie.

Time Wasn’t Saved—It Was Stolen

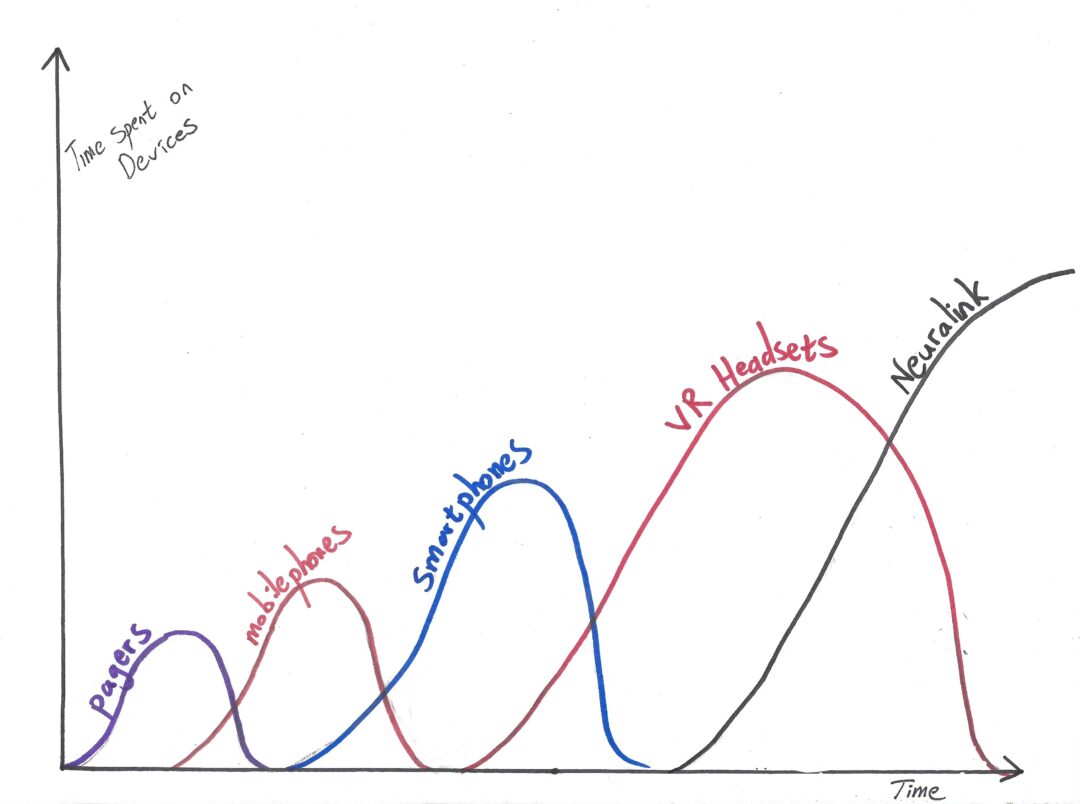

Look around. We are surrounded by technology—immersed in it, dependent on it, shaped by it. We carry tiny supercomputers in our pockets, we speak to algorithms more often than to our neighbors, and we spend our waking hours bathed in the blue light of glowing screens. But has any of it actually given us more time?

No. Technology hasn’t saved us time. It’s devoured it. Eaten it alive.

Then and Now: The Human Day, 50,000 Years Apart

Consider the life of a human 50,000 years ago. Their day was simple, direct, embodied. They walked, they hunted, they gathered. They made things with their hands, told stories under open skies, felt the rhythms of the seasons in their bones. They lived in time, not against it. Life was raw, yes—but it was real.

Now consider us. We wake up to alarms, not sunlight. We stare at screens for ten, twelve, fourteen hours a day. We sit in metal boxes on concrete roads, inching forward in traffic, breathing in fumes, scrolling to escape. We work jobs we hate to afford things we don’t need. We live in artificial environments, ruled by artificial schedules, chasing artificial goals. We have “smart” homes, “smart” phones, “smart” everything—except our lives, which feel increasingly hollow, anxious, and disconnected.

Efficiency as an Illusion

Instead of walking for three hours through the forest, we spend three hours trapped in a car. Instead of spending our days gathering food and sharing it with a tribe, we work nine to five in front of lifeless monitors just to afford a plastic-wrapped steak from Costco. Instead of learning how to live with the land, we spend decades learning how to operate machines—how to update software, how to decode cryptic settings menus, how to keep pace with the next new thing.

Technology doesn’t save us time. It only repackages it, monetizes it, demands more of it. For every hour we “save,” we give another away to maintenance, to learning curves, to constant adaptation. The illusion of progress blinds us to the reality of our loss.

We’ve Forgotten How to Be Human

And that loss runs deeper than just time. We are forgetting how to be human.

We have lost the capacity to feel. To be still. To sit in silence and listen to the wind. We’ve become emotionally illiterate, numb, overstimulated. We swipe and scroll instead of speak. We capture memories instead of living them. We consume endless streams of information but forget how to truly know anything—or anyone.

We are so rarely present. Always elsewhere. Always online.

The Emotional Fallout of a Disconnected Age

We cannot feel the now because we’re always running from it. And when the weight of it catches up, when the stress becomes unbearable, we medicate. We reach for science-based antidepressants to dull the ache of a life that was never meant to be lived this way. We design machines to comfort us, apps to cheer us up, filters to make us look alive.

But inside, we’re not alive. We’re surviving. Performing. Fragmenting.

The Real Meaning of Freedom

The promise of technology was freedom. But freedom is not found in faster downloads or smarter devices. Freedom is in presence. In connection. In the slow, quiet moments that technology has trained us to abandon.

This isn’t a rejection of all innovation. It’s a reckoning. A moment to pause and ask: what have we really gained? And what have we lost?

What If We’ve Been Asking the Wrong Questions?

Maybe we don’t need more speed. Maybe we need more stillness.

Maybe we don’t need more tools. Maybe we need more touch.

Maybe the answer isn’t out there in the next device, the next upgrade, the next fix.

Maybe the answer is behind us—somewhere in the forest, somewhere in the silence, somewhere in the simple act of being alive and awake and here.

Discover more from Brin Wilson...

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.